Approximately 80 percent of the U.S. population and more than 90 percent of the nation’s physicians reside in urban areas (1, 2). While cities are central to many cultural, economic, and transportation activities, these densely populated and interconnected centers can become vulnerable to infectious disease outbreaks and other health crises(3, 4). Interoperable health information technology (IT) can play an important role in responding to these events. Prior research examined interoperability among hospitals at the national level, but little is known about rates of interoperability within U.S. cities. This data brief describes variation in interoperability among hospitals within 15 major U.S. combined statistical areas (CSAs), hereafter referred to as cities. We highlight differences in interoperability between cities in terms of hospitals’ ability to perform four key domains of interoperability. These domains are find, send, receive, and integrate electronic health information with sources outside their health system. We also present findings on participation in health information exchanges (HIEs), variation in interoperability by hospital characteristics, and the association between interoperability and having information available at the point of care.

HIGHLIGHTS

- Major U.S. cities have high rates of interoperability of health data, but variation exists.

- Hospitals’ engagement in interoperability improved by more than 50 percent in 8 major U.S. cities since 2015.

- Hospitals that participate in an HIE and possess the dominant health IT developer’s EHR software within a city are more likely to engage in interoperability and have information available than hospitals with neither.

- Small and independent hospitals in major U.S. cities trail their counterparts in terms of interoperability and providers having information available at the point of care.

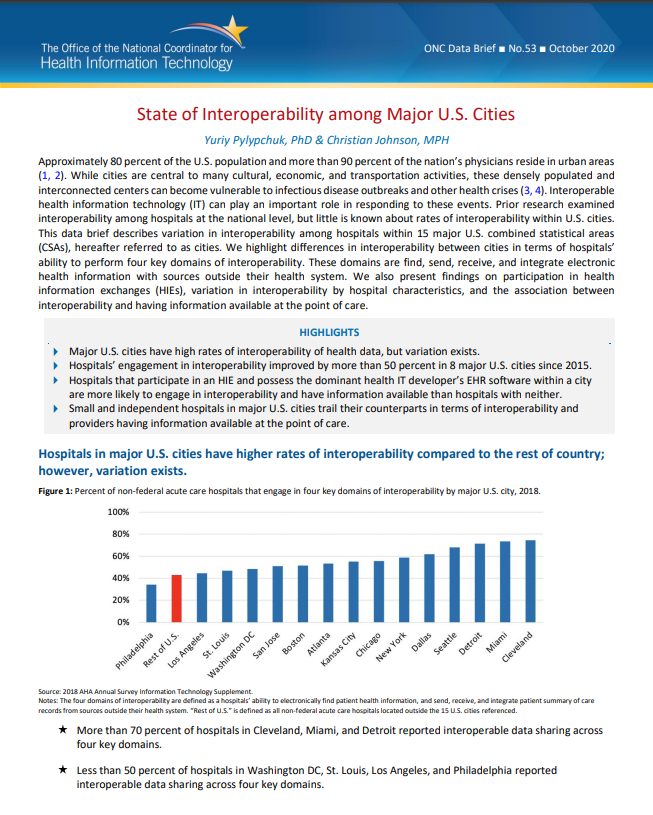

Hospitals in major U.S. cities have higher rates of interoperability compared to the rest of country; however, variation exists.

Figure 1: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals that engage in four key domains of interoperability by major U.S. city, 2018.

Source: 2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement

Notes: The four domains of interoperability are defined as a hospitals’ ability to electronically find patient health information, and send, receive, and integrate patient summary of care records from sources outside their health system. “Rest of U.S.” is defined as all non-federal acute care hospitals located outside the 15 U.S. cities referenced.

★ More than 70 percent of hospitals in Cleveland, Miami, and Detroit reported interoperable data sharing across four key domains.

★ Less than 50 percent of hospitals in Washington DC, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia reported interoperable data sharing across four key domains.

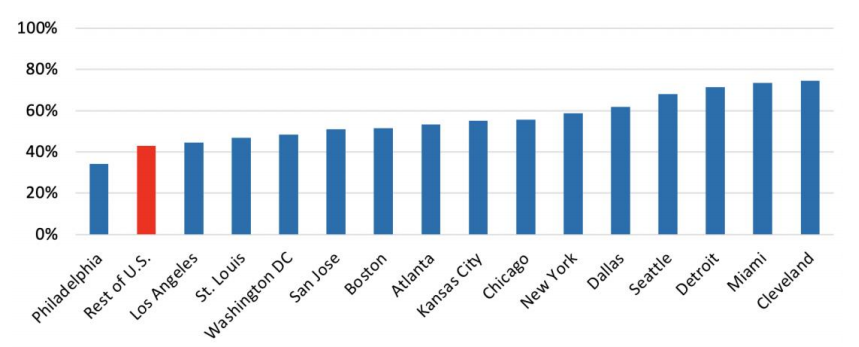

Hospitals’ engagement in four key domains of interoperability improved by more than 50 percent in eight major U.S. cities between 2015 and 2018.

Figure 2: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals in major U.S. cities that engage in four key domains of interoperability by change in interoperability from 2015 to 2018.

Source: 2015-2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement.

★ Cities with similar levels of interoperability experienced different rates of improvement from 2015 to 2018.

★ The proportion of hospitals engaging in interoperability improved by more than 100 percent in Chicago, New York, and Boston between 2015 and 2018.

★ The proportion of hospitals engaging in interoperability improved by less than 15 percent in Seattle and Atlanta between 2015 and 2018.

★ Three cities (Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and St. Louis) demonstrated small rates of improvement in interoperability and low rates of performing four key domains of interoperability in 2018.

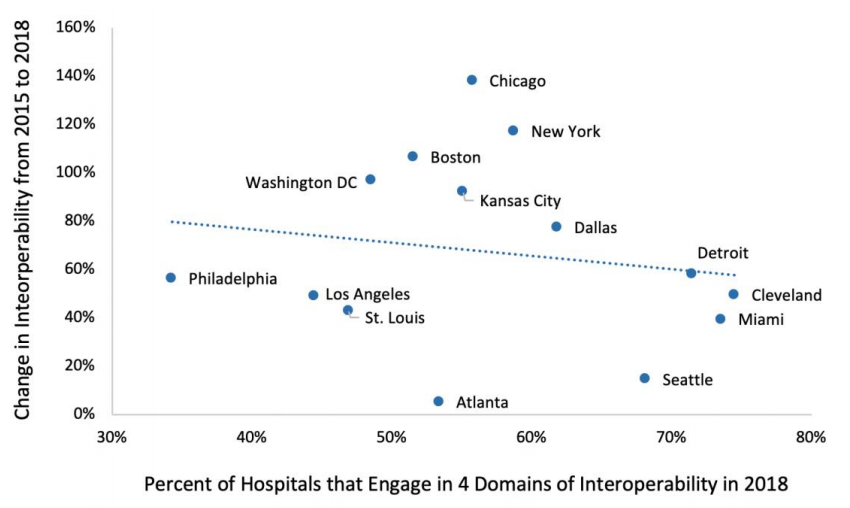

Cities with a larger proportion of hospitals engaging in four key domains of interoperability reported higher rates of providers having information available at the point of care.

Figure 3: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals in major U.S. cities that report their providers have information available at the point of care by hospital engagement in four key domains of interoperability, 2018.

Source: 2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement.

★ More than 70 percent of hospitals reported that providers have information available at the point of care in Miami, Detroit, Cleveland, and Washington DC.

★ Philadelphia had the lowest proportion of hospitals engaging in our key domains of interoperability and providers having information available at the point of care.

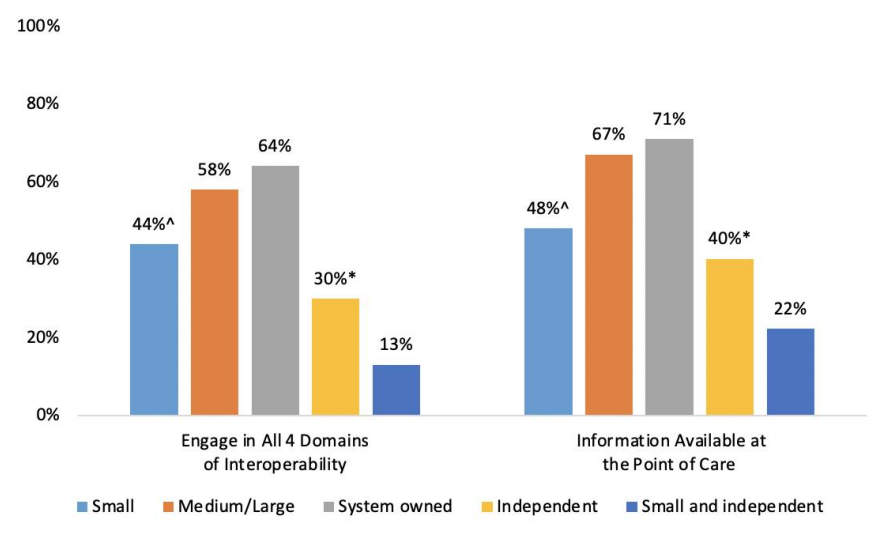

The percent of hospitals in large U.S. cities engaging in four key domains of interoperability varies by hospital type.

Figure 4: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals in major U.S. cities that engage in four key domains of interoperability by hospital type, 2018

Source: 2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement.

Notes: ^Significantly different from medium/large (p<0.05). *Significantly different from system owned (p<0.05)

★ Small hospitals were less likely to engage in interoperability and have information available at the point of care than medium/large hospitals.

★ System owned hospitals had the highest rates of interoperability (64%) and providers having information available at the point of care (71%) with major U.S. cities.

★ Small and independent hospitals lagged behind system owned hospitals in rates of interoperability (over four times) and providers having information available at the point of care (over three times) within major U.S. cities.

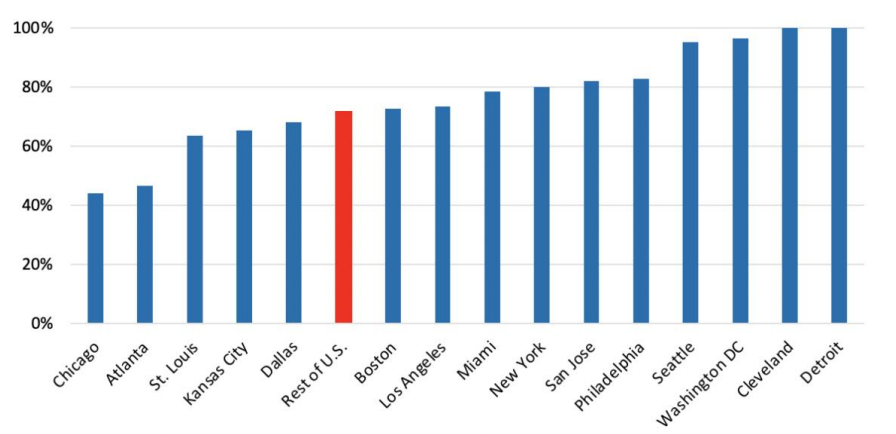

Hospitals’ participation in state, regional, or local HIEs varies widely across major U.S. cities.

Figure 5: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals in major U.S. cities that participate in a state, regional, or local health information exchange organization, 2018.

Source: 2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement.

Note: “Rest of U.S.” is defined as all non-federal acute care hospitals located outside the 15 U.S. cities referenced

★ Nearly all hospitals in Seattle, Washington DC, Detroit, and Cleveland reported participating in a state, regional, or local HIE.

★ Less than 50 percent of hospitals in Chicago and Atlanta reported participating in a state, regional, or local HIE.

★ Five major U.S. cities had a lower proportion of hospitals participating in state, regional, or local HIEs than the rest of the country.

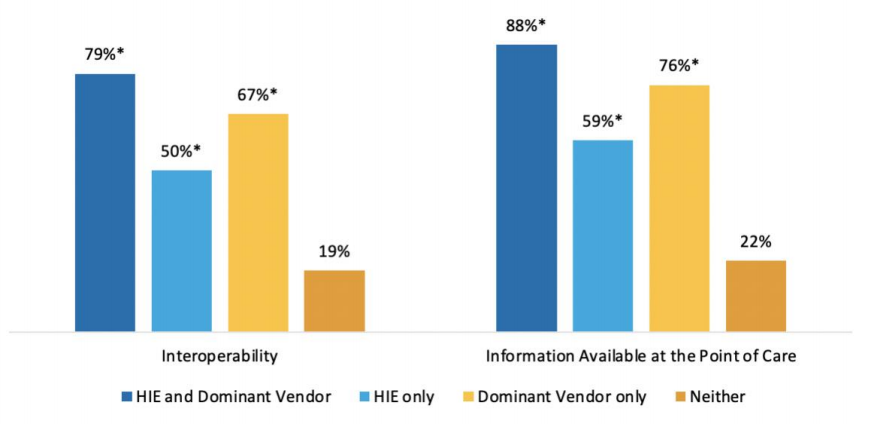

Hospital interoperability increases with HIE participation and health IT developer footprint in the city.

Figure 6: Percent of non-federal acute care hospitals in major U.S. cities that engage in four key domains of interoperability and have information available at the point of care by participation in HIE and having a dominant health IT developer, 2018.

Source: 2018 AHA Annual Survey Information Technology Supplement.

Notes: Dominant health IT developer is defined as the EHR developer with the largest market share in a given city. *Significantly different from “Neither” group (p<0.05).

★ Participation in a HIE and having an EHR from the dominant health IT developer within a city leads to the highest rates of interoperability and providers having information available at the point of care than in any other presented categories.

★ Hospitals that participate in HIEs but do not have an EHR from the dominant health IT developer within a city are less likely to engage in interoperability than hospitals with dominant health IT developer but without HIE participation.

★ Among hospitals that neither participate in a HIE nor have the dominant health IT developer within a city, only one out of five hospitals engaged in interoperability.

Summary

Seamless and timely exchange of electronic health information can improve health outcomes and lower health care cost. In particular, interoperable exchange has been found to reduce unplanned readmissions and duplicate testing (5, 6). In the case of infectious disease outbreaks and other health crises, interoperability is an essential tool for treating patients and coordinating care across providers. Inability to effectively exchange electronic health information can have significant implications on patient outcomes and public health.

Although much has been written about national trends in interoperability (7), little is understood about the levels of interoperability within major U.S. cities and their overall health IT infrastructure. Understanding variation in interoperability across cities and its sources of inequality is an important issue as it reveals readiness of U.S. cities in addressing health crises and highlights areas of need. In this data brief, we present statistics on levels of interoperability, participation in HIEs, and availability of information at the point of care across 15 major U.S. cities.

Rates of interoperability, participation in HIE, and providers having information available at point of care varies widely across U.S. cities. For example, hospitals in Cleveland, Detroit, and Seattle reported higher rates of interoperability, HIE participation, and providers having information available at the point of care compared to hospitals in Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Los Angeles. The proportion of hospitals engaged in interoperability in Cleveland was two times higher (75 percent) than the proportion of hospitals in Philadelphia (34 percent). Similarly, nearly all hospitals in Seattle, Washington DC, Detroit and Cleveland participated in state, regional, or local HIEs while less than 50 percent of hospitals participate in Chicago and Atlanta. Washington DC reported the highest rates of hospitals having information available at the point of care (90 percent) while in Philadelphia and Kansas City only about half of hospitals reported that their providers had information available at the point of care.

The proportion of hospitals engaging in four key domains of interoperability improved by more than 50 percent in eight of the 15 major U.S. cities between 2015 and 2018. However, three cities (Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and St. Louis) demonstrated both slow improvements and low levels of interoperability, implying uneven growth in interoperability across the country. City-level data indicate that cities with a larger proportion of hospitals engaging in interoperability have higher rates of providers with information available at the point of care. This implies that cities with high levels of interoperability could be more prepared to make data driven decisions in the event of health crises.

Cities’ rates of interoperability and providers having information available at the point of care also varied widely by hospital type and health IT infrastructure within the city. System owned hospitals reported the highest rates of interoperability (64 percent) and having information available at the point of care (71 percent). Small and independent hospitals in major cities face significant challenges in terms of interoperability with only about one in eight of these hospitals engaging in four key domains of interoperability (find, send, receive, and integrate). Participation in state, regional, or local HIEs and having an EHR from the health IT developer with the largest market share in a city can improve rates of interoperability and providers having information available at the point of care.

Electronic health information exchange is critical to ensuring timely information is available when and where it is needed. The 21st Century Cures Act (8), sought to improve the flow and exchange of electronic health information by prohibiting information blocking, enhancing the usability and accessibility of health IT, and creating a Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) to improve data sharing between HIEs. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) recently finalized rulemaking to adopt many of these provisions in the Cures Act. Together, these activities have the potential to improve access and exchange of electronic health information, and to give providers the necessary information to treat patients in a timely manner.

Definitions

Non-federal acute care hospital: Hospitals that meet the following criteria: acute care general medical and surgical, children’s general, and cancer hospitals owned by private/not-for-profit, investor-owned/for-profit, or state/local government and located within the 50 states and District of Columbia.

Interoperability: The ability of a system to exchange electronic health information with and use electronic health information from other systems without special effort on the part of the user. This brief further specifies interoperability as the ability for health systems to electronically send, receive, find, and use health information with other electronic systems outside their organization.

Integrate: Whether the EHR integrates summary of care record received electronically (not eFax) from providers or sources outside your hospital system/organization without the need for manual entry.

Find: Whether providers at your hospital query electronically for patients’ health information (e.g., medications, outside encounters) from sources outside of your organization or hospital system.

Small hospital: Non-federal acute care hospitals of bed sizes of 100 or less. Health information exchanges (HIE): State, regional, or local health information network. This does not include local proprietary or enterprise networks.

Intensive care unit (ICU) beds: Hospital beds available in medical/surgical, cardiac, and “other” ICUs. The” other” category consists mostly of neurology and trauma ICUs.

Dominant Health IT Developer EHR: EHR adopted by hospitals from a health IT developer with the largest market share within a city.

Detailed Description of CSAs.

| CSA Code | Full name | Abbreviated name |

|---|---|---|

| 122 | Atlanta-Athens-Clarke County-Sandy | Atlanta |

| 148 | Boston-Worcester-Providence | Boston |

| 176 | Chicago-Naperville | Chicago |

| 184 | Cleveland-Akron-Canton | Cleveland |

| 206 | Dallas-Fort Worth | Dallas |

| 220 | Detroit-Warren-Ann Arbor | Detroit |

| 312 | Kansas City-Overland Park | Kansas City |

| 348 | Los Angeles-Long Beach | Los Angeles |

| 370 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Port St. Lucie | Miami |

| 408 | New York-Newark | New York |

| 428 | Philadelphia-Reading-Camden | Philadelphia |

| 476 | San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland | San Jose |

| 488 | Seattle-Tacoma | Seattle |

| 500 | St. Louis-St. Charles-Farmington | St. Louis |

| 548 | Washington-Baltimore-Arlington | Washington DC |

Data Source and Methods

Data are from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Information Technology (IT) Supplement to the AHA Annual Survey. Since 2008, ONC has partnered with the AHA to measure the adoption and use of health IT in U.S. hospitals. ONC funded the 2018 AHA IT Supplement to track hospital adoption and use of EHRs and the exchange of clinical data.

The chief executive officer of each U.S. hospital was invited to participate in the survey regardless of AHA membership status. The person most knowledgeable about the hospital’s health IT (typically the chief information officer) was requested to provide the information via a mail survey or secure online site. Non-respondents received follow-up mailings and phone calls to encourage response.

The survey was fielded from the beginning of January 2019 to the middle of May 2019. The response rate for non-federal acute care hospitals was 64 percent. A logistic regression model was used to predict the propensity of survey response as a function of hospital characteristics, including size, ownership, teaching status, system membership, and availability of a cardiac intensive care unit, urban status, and region. Hospital-level weights were derived by the inverse of the predicted propensity.

References

- United States Census Bureau. New Census Data Show Differences between Urban and Rural Populations. December 08, 2016. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2016/cb16-210.html

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Distribution of the U.S. Primary Care Workforce. (July 2018). Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/primary/pcwork3/index.html

- Bell D, Weisfuse I, Hernandez-Avila M, del Rio C, Bustamante X, and Rodier G. Pandemic Influenza as 21st Century Urban Public Health Crisis. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2009 Dec; 15(12): 1963–1969.

- Ali SH, Keil R. Contagious Cities. Geography Compass. (September 2007). 1(5).

- Chen M, Guo S, Tan X. Does Health Information Exchange Improve Patient Outcomes? Empirical Evidence From Florida Hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(2):197-204.

- Ayabakan S, Bardhan I, Zheng Z, Kirksey K. The impact of health information sharing on duplicate testing. MIS Quarterly. 2017. Vol. 41 No. 4, pp. 1083-1103.

- Pylypchuk Y., Johnson C., Patel V. (March 2020). State of Interoperability and Methods Used for Interoperable Exchange among U.S. Non-federal Acute Care Hospitals in 2018. ONC Data Brief, no.51. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC.

- 21st Century Cures Act. H.R. 34, 114th Congress. 2016. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW114publ255/pdf/PLAW-114publ255.pdf. Accessed: February 1, 2017

Acknowledgements

The authors are with the Office of Technology, within the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. The data brief was drafted under the direction of Mera Choi, Director of Technical Strategy and Analysis, and Talisha Searcy, Director of the Data Analysis Branch.

Suggested Citation

Pylypchuk Y. & Johnson C. (October 2020). State of Interoperability among Major U.S. Cities. ONC Data Brief, no.53. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology: Washington DC

Appendix Table A1: Survey questions assessing variation in interoperability among hospitals.

| Question Text | Response Options |

|---|---|

| When a patient transitions to another care setting or organization outside your hospital system, how often does your hospital use the following methods to send a summary of care record? |

Often | Sometimes| Rarely |Never | Don’t Know/NA Methods without intermediaries • Mail or fax • eFax using EHR • Provider portal for view only access to EHR system • Interface connection between EHR systems (e.g. HL7 interface) • Direct access to EHRs (via remote or terminal access) Methods with intermediaries • Standalone HISP or HISP provided by a third party that enables secure messaging (such as DIRECT) Regional, state, or local health information exchange organization (HIE/HIO). NOT local proprietary, enterprise network • EHR vendor-based network that enables exchange with vendor’s other users (e.g. Epic’s Care Everywhere) • National networks that enable exchange across different EHR vendors ( e.g. CommonWell, e-Health Exchange, Carequality) |

| When a patient transitions to another care setting or organization outside your hospital system, how often does your hospital use the following methods to receive a summary of care record? |

Often | Sometimes| Rarely |Never | Don’t Know/NA Methods without intermediaries • Mail or fax • eFax using EHR • Provider portal for view only access to EHR system • Interface connection between EHR systems (e.g. HL7 interface) • Direct access to EHRs (via remote or terminal access) Methods with intermediaries • Standalone HISP or HISP provided by a third party that enables secure messaging (such as DIRECT) Regional, state, or local health information exchange organization (HIE/HIO). NOT local proprietary, enterprise network • EHR vendor-based network that enables exchange with vendor’s other users (e.g. Epic’s Care Everywhere) • National networks that enable exchange across different EHR vendors ( e.g. CommonWell, e-Health Exchange, Carequality) |

| Do providers at your hospital query electronically for patients’ health information (e.g. medications, outside encounters) from sources outside of your organization or hospital system? |

• Yes • No, but do have the capability • No, don’t have capability • Do not know |

| How often are the following electronic methods used to search for (e.g., query or auto-query) and view patient health information from providers outside your hospital system? |

Often | Sometimes| Rarely |Never | Don’t Know/NA • Provider portals to view records in another EHR system • Interface connection between EHR systems (e.g. HL7 interface) • Direct access to EHRs (via remote or terminal access) • Regional, state, or local health information exchange organization (HIE/HIO). NOT a local proprietary, enterprise network • EHR vendor-based network that enables record location within the network (e.g. Care Everywhere) • EHR connection to national networks that enable record location across EHRs in different networks (e.g. Commonwell, e-Health Exchange, Carequality • Other |

| Does your EHR integrate the information contained in summary of care records received electronically (not eFax) without the need for manual entry? Note: This refers to the ability to add or incorporate the information to the EHR without special effort (this does NOT refer to automatically adding data without provider review). This could be done using software to convert scanned documents into indexed, discrete data that can be integrated into EHR. |

• Yes, routinely • Yes, but not routinely • No • Do not know • NA |

| Do providers at your hospital routinely have necessary clinical information available electronically (not e-Fax) from outside providers or sources when treating a patient that was seen by another health care provider/setting? |

• Yes • No • Do not know |

| Please indicate your level of participation in a state, regional, and/or local health information exchange (HIE) or health information organization (HIO). Note: this does not refer to a private, enterprise network. |

• HIE/HIO is operational in my area and we are participating and actively exchanging data in at least one HIE/RHIO • HIE/HIO is operational in my area but we are not participating • HIE/HIO is not operational in my area • Do not know |